‘I can’t simply afford to give my children what they really need in terms of food,’ said Feyintola Bolaji, a mother of three in her 50s based in Nigeria’s southwestern city of Ibadan.

Nigerian merchant Feyintola Bolaji, struggling with stagnant earnings and dwindling sales, is now being squeezed by the ever increasing prices demanded by her food suppliers, leading her to cut down on the amount she can put on her own family’s table.

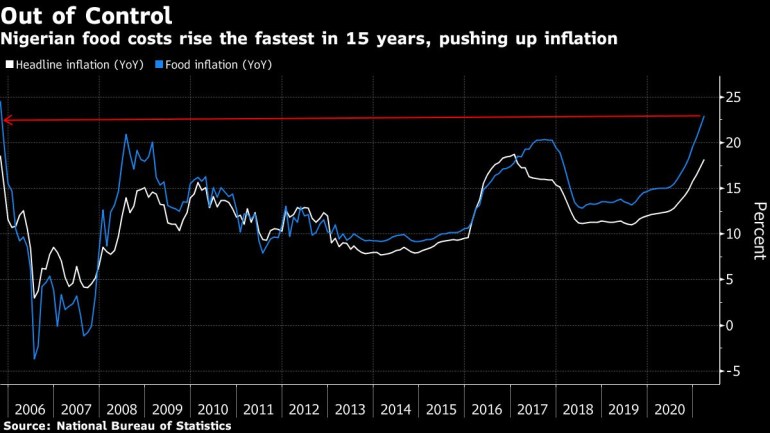

Bolaji’s belt tightening is being shared by millions across Africa’s most populous nation. Not long after Nigeria’s statistics agency revealed that one in three people in the continent’s largest economy were unemployed, on Thursday it announced that food inflation has accelerated at the highest pace in 15 years, compounding the misery of many households.

“It is really bad, I can’t simply afford to give my children what they really need in terms of food,” said Bolaji, a mother of three in her 50s based in the southwestern city of Ibadan. “I try to make them get the nutrients they need as growing children, but it is not enough,” she said, adding “I have had to cut down on meat and fish.”

Insurgency, unrest, and the stand of President Muhammadu Buhari’s government on food imports in a nation where more than half the population lives on less than $2 a day are worsening food insecurity in the African country. Meanwhile, the coronavirus pandemic has robbed 70% of Nigerians of some form of income, according to a Covid-19 impact survey published by the statistics agency last month.

Food inflation rose to 22.95% in March, caused by wide-ranging price increases across items such as cereals, yam, meat, fish and fruits. Those soaring costs have been in part blamed on a worsening conflict between farmers and herders in Nigeria’s agriculture belt that Buhari has struggled to quash.

The unrest, combined with the more than decade-long Boko Haram insurgency in the north, a weakening currency and higher fuel prices have also contributed to rising food prices, according to SBM Intelligence, a Nigerian research firm.

The situation has also been exacerbated by import restrictions on certain staples, such as rice, that have remained in place despite Buhari reopening Nigeria’s land borders in December following a 16-month shutdown in an attempt to end rampant smuggling.

Rising inflation has adversely affected the profitability of producers and is a major contributor to the low export penetration of made-in-Nigeria goods in the international market, the Manufacturers Association of Nigeria said in a statement on Friday.

“There is an urgent need for government to intentionally ensure price stability before the situation becomes deplorable,” the manufacturing body said.

Food prices will remain elevated until the security crisis, which has prevented farmers from returning to their land, is resolved, said Cheta Nwanze, a lead partner with SBM Intelligence. That’s “unless the government does the sensible thing and allows food imports to happen,” he said.

Until then Nigerians, who already spend more than half their earnings on food, have had to cut down. Just over 50% of all households reported reduced consumption between July and December last year due to the twin pressures of falling wages and rising food costs, according to Nigeria’s statistics agency.

Kemi Adedigba, a 42-year-old freelance writer living in Lagos, the country’s financial hub, is among those who has been hit by that double-whammy. Adedigba has two growing teenagers to feed, but is struggling with a steady drop in work even as her monthly food bill climbed by almost 70% since December.

“You are lucky if you get recurring gigs with the way the economy is going down the toilet,” she said. “It is a nightmare.”